Today we’re examining an intriguing firearm with a fascinating history. It is difficult to understate the potential importance of the Curtis Rifle. Despite being designed in Britain in the 1860s the firearm gained more notoriety when it was offered as evidence in a legal battle between the Winchester Repeating Arms company and Francis Bannerman. What makes the firearm most noteworthy, however, is its fundamentally unconventional layout. Designed by William Joseph Curtis in the mid-1860s, it is arguably one of the earliest ‘bullpups’ and almost certainly the first repeating bullpup.

For the purpose of this article it would be wise to first define what a bullpup actually is. It can be defined as a weapon with a somewhat unconventional layout which places the action and magazine behind the weapon’s trigger group. This has the benefit of maintaining a conventional rifle’s barrel length while making the overall length of the rifle more compact.

Bullpup rifles became popular with a number of militaries around the world during the 1970s and 1980s – namely the Austrian Steyr AUG, the French FAMAS and the British SA80, and more recently with rifles from China and Singapore as well as the Tavor series of rifles from Israel.

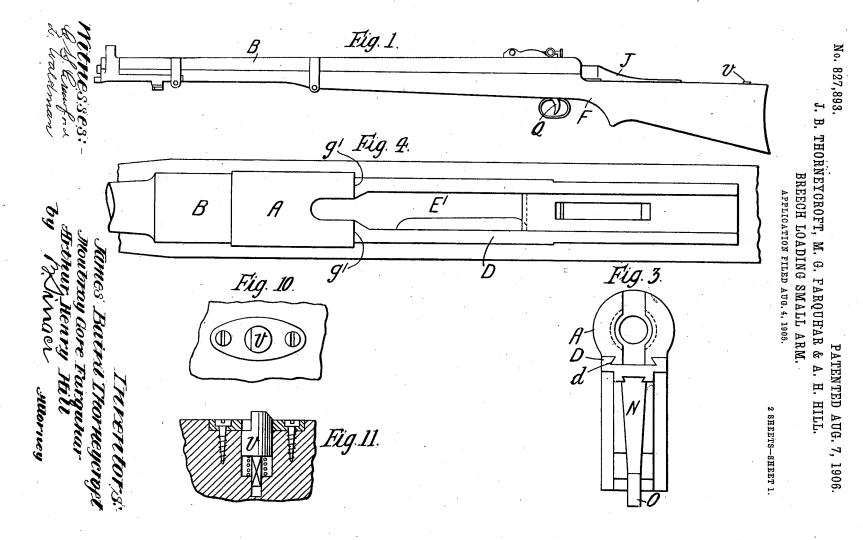

The bullpup, however, dates back much further with some argument to be made for the first firearms to utilise the concept being 19th century percussion target shooting rifles. The earliest military bullpups date to the beginning of the 20thth century, these include a rifles designed by Samuel McClean, the initial designer of the Lewis Gun, patented in 1896 (US #723706), by Major Philip Godsal (US #808282) and a carbine developed by James Baird Thorneycroft in 1901. Thorneycroft subsequently worked with Moubray Gore Farquhar and Arthur Henry Hill to patent a refined version of the carbine in 1905 (US #827893). While the Thorneycroft was tested by the British army it was rejected due to ergonomic and reliability shortcomings.

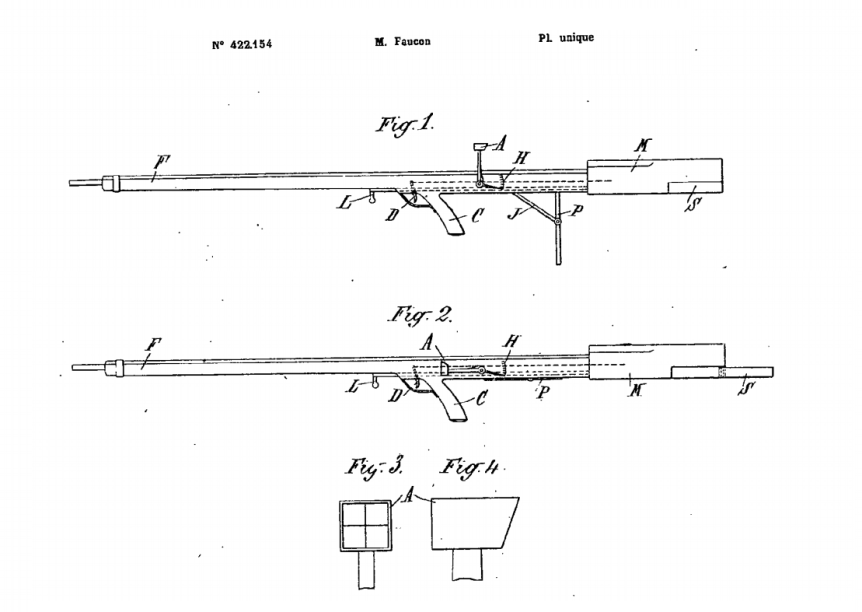

In 1908 Lieutenant-Colonel Armand-Frédéric Faucon of the Troupes Coloniales (French Colonial Infantry) began developing what he termed a ‘Fusil Équilibré’ or balanced rifle. Faucon patented his concept in France in 1911 (FR #422154) and continued to work on the balanced rifle during World War One, utilising a Meunier A5 semi-automatic rifle in working prototypes. The Faucon-Meunier rifle was tested in 1918 and 1920 but eventually rejected. It would be nearly 45 yeas before the bullpup concept was revisited by a major power. Engineers working at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield and at the British Armament Design Department in the 1940s began to develop designs based around the bullpup concept. (Some of these will hopefully be the focus of future videos!)

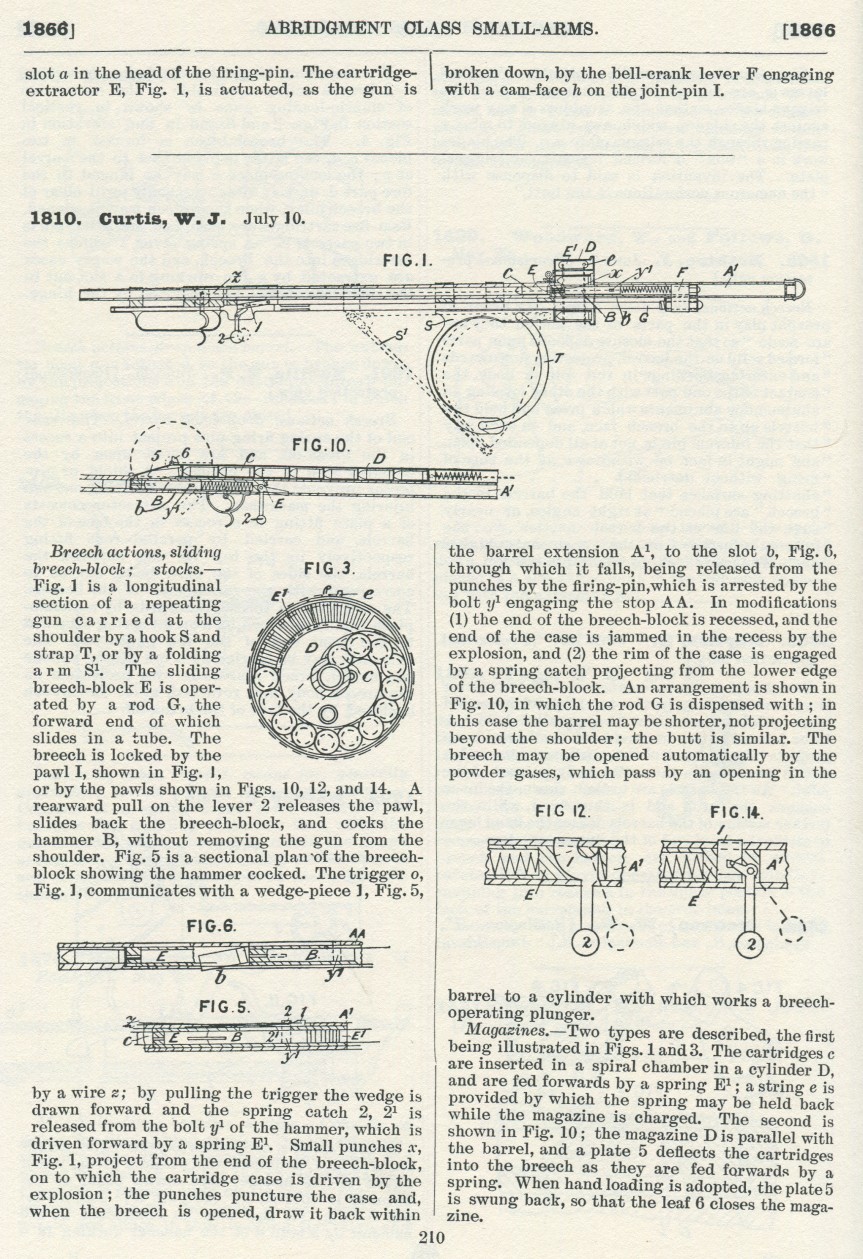

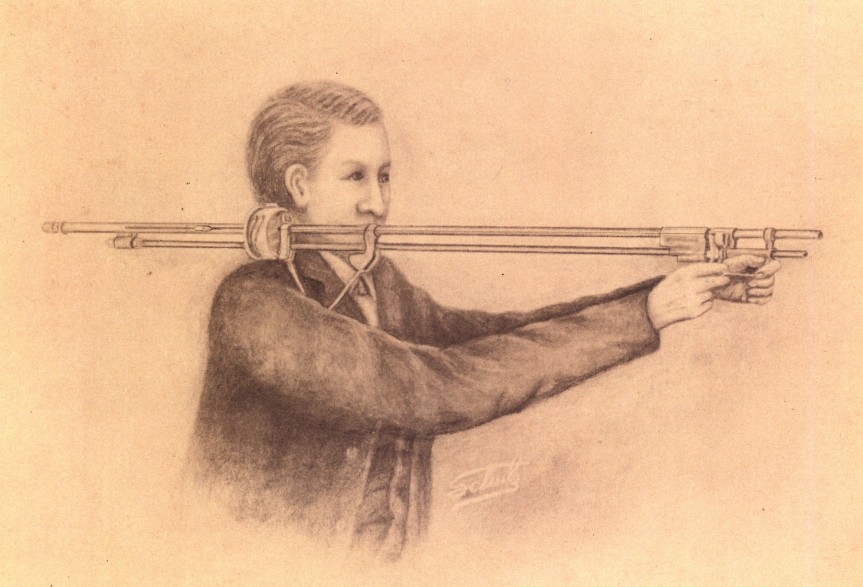

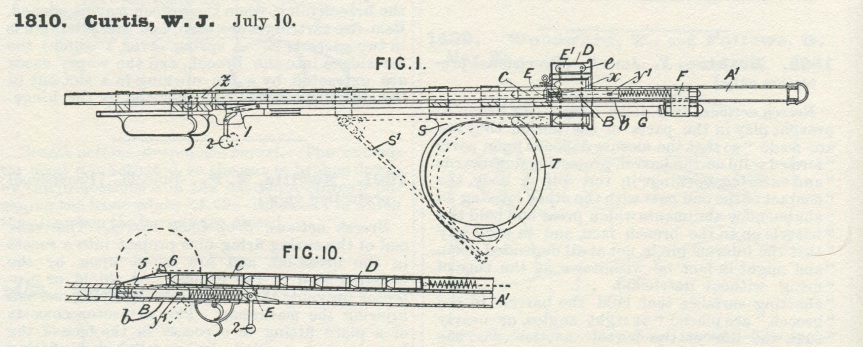

William Curtis’ design, however, predates all of these. Patented in Britain on 10th July, 1866, Curtis is listed by the London Gazette as a Civil Engineer. His design is unlike anything that had been seen before. Based on a slide-action with a drum magazine, it was placed over the shoulder – much like a modern shoulder-fired anti-tank weapon.

Curtis’ rifle is probably the very first bullpup magazine rifle, one of the earliest to have a drum magazine (an Italian, Marco Antonio Francois Mennons, patented an earlier design for a drum magazine in March 1862, GB #637) and also an early striker-fired design. Clearly a design well ahead of its time and radically unconventional.

This unconventional gun’s designer was born in Islington, London in 1802, as a civil engineer he worked on Britain’s rapidly growing railway network. He died in 1875, placing the development of his rifle nearer the end of his life. With hindsight Curtis’ design clearly had revolutionary potential but it appears that his concept was never taken up. It appears that he only patented his design in the United Kingdom. If not for a corporate lawsuit on another continent, decades later, then it is possible Curtis’ design, like so many others, would have slipped into historical obscurity.

Francis Bannerman vs. the Winchester Repeating Arms Company

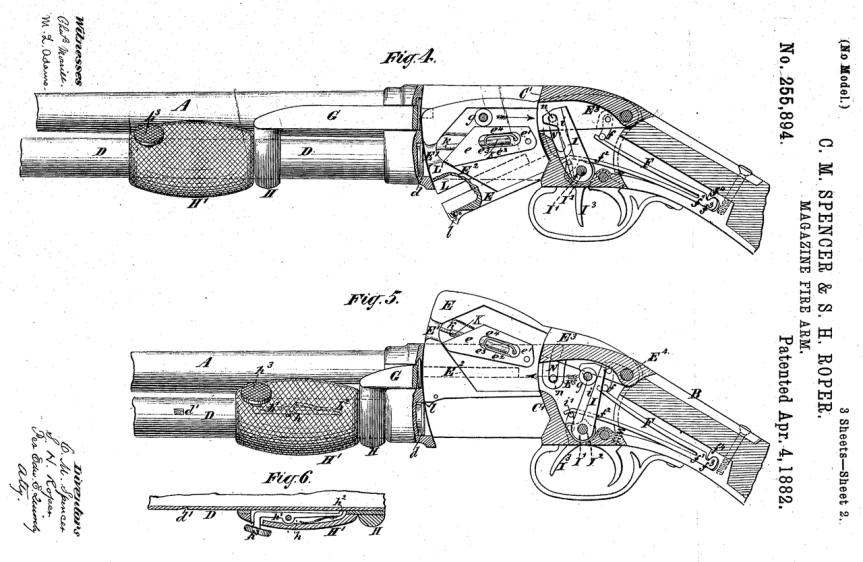

In 1890, Francis Bannerman VI, a successful entrepreneur specialising in junk, scrap and later surplus, purchased the Spencer Arms Company and the rights to their patents. The company had been founded by Christopher Miner Spencer, designer of the Spencer Rifle, they produced the first commercially successful slide or pump-action shotgun. This pump action shotgun was designed by Spencer and Sylvester H. Roper and patented in April, 1882 (US #255894). Bannerman continued producing the shotgun as the Bannerman Model 1890, however, in 1893 the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, introduced the John Browning-designed Model 1893 pump shotgun (US #441,390).

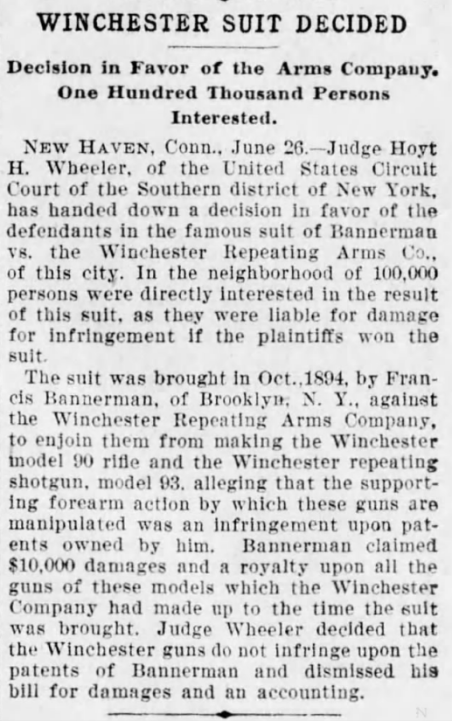

In response in October 1894, Bannerman filed a law suit against the Winchester Repeating Arms Company claiming that the slide/pump actions used by Winchester’s Model 1890 and new Model 1893 shotgun infringed on the patents that he owned.

He called for the court to force Winchester to halt production and claimed $10,000 in damages and royalties for the sale of guns which he believed infringed his patent. Winchester temporarily halted production of the Model 1893, in the meantime Bannerman continued producing and improving his shotgun introducing the 1894 and 1896 models.

Various contemporary newspaper reports suggest between 100,000 and 500,000 people were directly interested in the case as ordinary owners were liable under the conditions of Bannerman’s suit.

Winchester dispatched George D. Seymour to Europe to scour the French and British patent archives for any patents for similar actions that had been filed there before those now owned by Bannerman. Winchester discovered four patents: three British and one French. The earliest of these was Alexander Bain’s patent of 1854. Two more patents held by Joseph Curtis and William Krutzsch were found, dating from 1866. The later French patent was filed by M.M. Magot in 1880. All of these designs, including the Curtis we are examining here, never progressed beyond the development stage and were largely forgotten until rediscovered by Winchester.

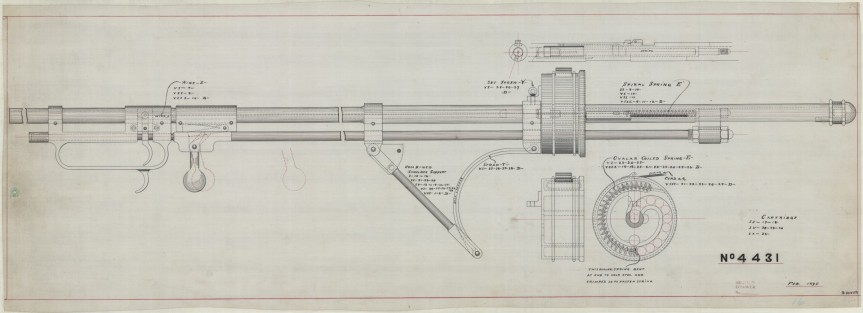

Winchester claimed that these earlier designs invalidated Bannerman’s patent claims. To illustrate their defence Winchester decided to build working models of each of the designs, breathing life into long forgotten patent drawings. This must have been a major engineering task as the patent designs would not have had all the information needed to produce a working model.

In 1895-96 Winchester engineers, including T.C. Johnson, assembled working models of each of the designs to prove their viability. These were tested and Winchester’s lawyers took them into court and submitted them as evidence, even offering a firing demonstration. The court declined the demonstration and made its decision on June 27th 1897. Judge Hoyt H. Wheeler of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled in favour of Winchester and threw out Bannerman’s suit.

Winchester had produced some 34,000 Model 1893s before, in November 1897, they introduced the improved Model 1897 which proved to be hugely popular on both the civilian and military markets. Bannerman unveiled a final shotgun, the Model 1900, but production ended in the early 1900s.

Curtis’ Unconventional Design

Curtis’ design encapsulates a number of features which, in 1866, were unheard of and arguably revolutionary. Not only is it probably the first magazine-fed repeating bullpup but it also uses a drum magazine, something that would not see substantial military use until the First World War. It has a folding shoulder support or stock, uses a striker fired action and makes use of self-contained ammunition.

The Curtis’ rifle is placed over the top of the user’s shoulder with a folding leather strap which fits into the shoulder pocket. Curtis’ original patent also suggests a fixed hook and strap. The user then grasps the loop near the muzzle with their support hand and the trigger and bolt handle with their other hand. Novel, but not the most ergonomic of designs.

The magazine appears to hold at least 13 or more rounds according to the available patent and Winchester’s engineering drawings. The magazine is fixed in place and rounds appear to have been fed into it through the loading/ejection port on the left side of the weapon. This would have also put spent cases being ejected right next to the user’s neck. Curtis’ patent explains that the magazine has a spring inside which has a length of string attached to the top of it which the user can pull back to depress it and allow cartridges to be loaded into the drum. The magazine has a single stack or loop of cartridges. Once loaded the string can be released, allowing the magazine spring to push rounds into the action.

The Curtis rifle’s action appears to lock at the front of the weapon with the bolt handle acting on a hinged, spring-loaded, locking piece or flapper which dropped into place when locked. To unlock the action the bolt handle was sharply pulled to the rear which pushed the locking piece out of engagement and unlocked the action allowing the operating rod to be cycled.

The weapon’s chamber appears to be just forward of the centre of the drum magazine with the striker assembly located behind it. To operate Curtis’ rifle the magazine was loaded and then the user had to unlock the action by pulling the bolt handle backwards. This then allowed the operating rod to be pulled backwards, like a pump action, which pushed the bolt and striker assembly to the rear, cocking the striker, the bolt handle was then returned forward and locked back into position. This chambered a round ready to be fired.

The trigger at the front of the firearm is connected to the striker assembly by a long length of wire. When pulled the wire becomes taught and trips a sear to release the striker, firing the weapon.

Originally Curtis’ patent describes how ‘small punches’ on the bolt face would pierce the cartridge base during firing to enable the spent case to be extracted once the action was cycled. From Winchester’s engineering drawings, however, it appears they replaced this with a more reliable and conventional extractor at the 7 o’clock position of the bolt face.

Given that the weapon would have fired black powder cartridges it is unclear how well the rifle would have faired with sustained firing. The drum magazine would have been susceptible to jamming as a result of powder fouling. This, however, would not have been an issue for Winchester later version of the rifle.

But the Curtis has one more interesting surprise. The original 1866 patent also includes what might be one of the earliest descriptions of a gas operated firearm. One of the most fascinating sections of Curtis’ original patent details how the rifle might have been adapted for gas operation:

“An arrangement is shown in Fig.10, in which the rod G is dispensed with; in this case the barrel may be shorter, not projecting beyond the shoulder; the butt is similar. The breech may be opened automatically by the powder gases, which pass by an opening in the barrel to a cylinder with which works a breech operating plunger.”

Curtis does not go into further detail but he is clearly describing a piston-driven, gas operated system. The patent drawing also depicts an alternative tube magazine instead of the drum magazine.

It is unknown if Curtis ever put his theory to the test and developed his gas system idea further. It is tempting to wonder if, in 1895 when Winchester were assembling their model of the Curtis, if John Browning or William Mason, who were also developing their own gas operated systems at the time, were aware of Curtis’ idea from 30 years earlier. As such Curtis’, admittedly vague, gas system pre-dates the first patents on gas operation by just under 20 years.

If you enjoyed the video and this article please consider supporting our work here.

Specifications:

Action: Slide action

Calibre: .32 Winchester Centre Fire

Feed: ~12 round drum magazine

My thanks to the Cody Firearms Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West for allowing me to examine and film the Curtis. Special thanks to the CFM’s assistant curator Danny Michael for making extra time to open up the case where the rifle Curtis is on display so we could examine it and for also sharing Winchester’s technical drawings and other records.

Thanks also to David Minshall of Research Press.co.uk for his assistance finding Curtis’ original British patent abridgement and to John Walter for digging up some additional information about Curtis’ life.

Bibliography:

‘Winchester Suit Decided’, The Times (Philadelphia), 27th June, 1897

‘Recollections of the Forming of the Pugsley & Winchester Gun Collections: A Talk Given by Mr. Edwin Pugsley at the New Haven Meeting of the AS of AC’, September, 1955.

Curtis Rifle, Cody Firearms Museum, online catalogue entry (source)

‘Francis Bannerman VI, Military Goods Dealer to the World’, American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin 82:43-50, D.B. Demeritt, Jr., (1982)

Patents:

Improvements in fire-arms’ A. Bain, British Patent #1404, 26th June, 1854

‘Breech actions, sliding breech block; stocks’, W.J. Curtis, British Patent #1810, 10th July, 1866

‘Breech actions, hinged and laterally-moving breech block; magazines’, W. Krutzsch, British Patent #2205, 27th August, 1866

‘Magazine Fire Arm’, Spencer & Roper, US Patent #255894, 4th April, 1882

‘Magazine Bolt Gun’, S. McClean, US Patent #723706, 28th May, 1896

‘Breech-loading small-arm’, P.T. Godsal, US Patent #808282, 19th June, 1903

‘Breech Loading Small Arm’, Thorneycroft, Farquhar & Hill, US Patent #827893, 4th August, 1905

‘Fusil équilibré’, A.B. Faucon, French Patent #422154, 15th March, 1911

9 thoughts on “The Curtis Rifle – The First Repeating Bullpup”